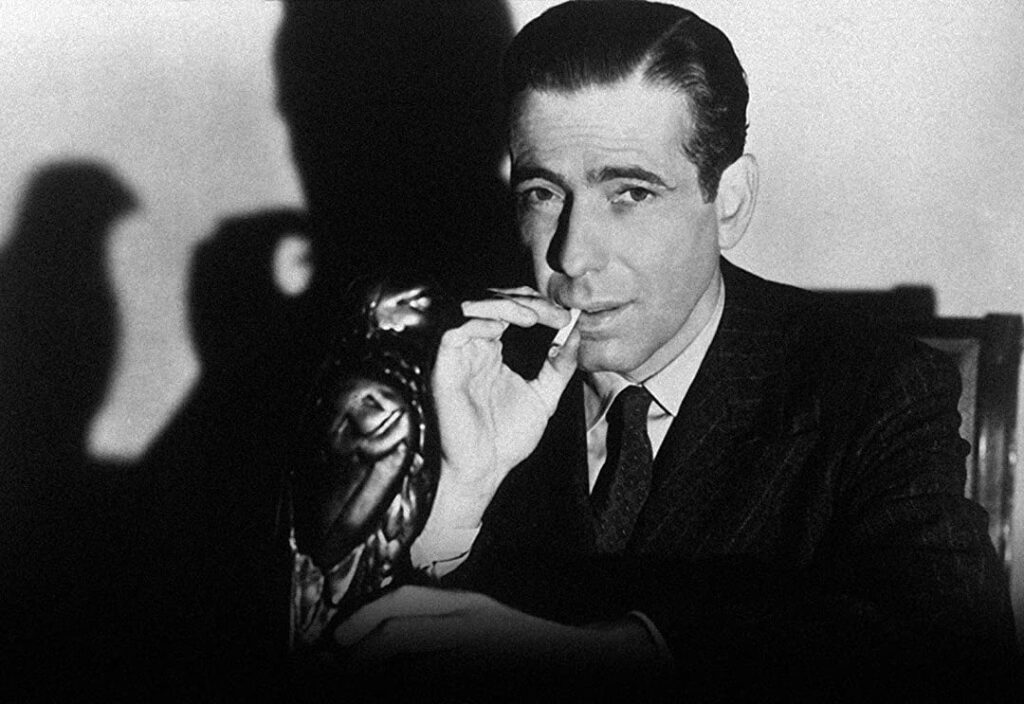

“I’ve no earthly reason to think I can trust you, and, if I do this and get away with it, you’ll have something on me that you can use whenever you want to. Since I’ve got something on you, I couldn’t be sure that you wouldn’t put a hole in me some day. All those are on one side. Maybe some of them are unimportant – I won’t argue about that – but look at the number of them. And what have we got on the other side? All we’ve got is that maybe you love me and maybe I love you.”

Sam Spade, The Maltese Falcon by Dashiell Hammitt

This passage from the Maltese Falcon is one of my favorite moments where our hero — Sam Spade — thinks aloud about the potential pitfalls of going in with femme fatale Brigid O’Shaughnessy in the climax of the novel. The obvious point of the monologue is to display Sam’s cold rationale as a private detective, which cannot be swayed even by someone he may have fallen in love with. What’s more, Sam’s obvious interest in Brigid’s offer is overpowered not by his moral code, but by his sense of self preservation.

As a reader and storyteller, I grapple with the concept of the antihero as a protagonist. I’m deeply suspicious when people throw around the terms “antihero” and “flawed character” because it’s often used to describe amoral characters who are hypercompetent and cruel for the sake of it with no real consequence.

We see the misuse of the term most often in comic books. Wolverine can be as big a jerk as he wants because he’s the best there is at what he does. He’s not all bad as a character and when writers decide to treat him like a stable adult human being that can use his words, he’s a great read. The problem is that he isn’t used this way very often. Why make him a fully realized person when he can just stab people, tell the chain of command to walk off a cliff, and obsess over married women? I intensely loathe that he’s as popular as he is because his popularity is centered around the erroneous perception that he’s an antihero. He’s not an antihero. He’s a vehicle of wish fulfillment for the worst kind of abuse that is the darkest corners of comic book fandom.

Side note: So glad these two have finally dealt with their sexual tension in the Hickman run.

Same goes for the Punisher. Frank Castle is not an antihero. He is a psychopath with untreated PTSD. Though, I like what they did with him with the Cosmic Ghostrider stuff.

John Constantine is one of the best antiheroes in comics, as illustrated time and again in how he is smart enough to see the big picture, but never from the right angle. He’s constantly making mistakes that further complicate his life and harm those around him. On top of that, he’s painfully aware of his mistakes and their consequences and he’s riddled with guilt that he hides behind cigarettes and sarcasm.

To say that antiheroes should not embody those characteristics we associate with classically heroic characters is a given. To say that they can be cynical and selfish is fair. However, a proper antihero is never completely devoid of empathy or morality. Possessing these qualities doesn’t automatically make a character heroic, but they do allow readers an emotional anchor to hold on to. They make these characters human. A good antihero still has a conscience. It’s a nuisance, but it’s there, even if their primary reason to do the right thing, is just so they can live with themselves. What makes a good antihero interesting is that they find themselves in situations where they want to do the right thing, but they can’t get out of their own way. Their inherent nature is an obstacle in their journey. They can’t communicate effectively. They don’t trust others. In a lot of ways a good antihero is their own antagonist. The things that make life easier when the going gets rough is our personal relationships. Friends, family, lovers, allies. Antiheroes have very few allies, and often put themselves at odds with those few close to them for petty or short-sighted reasons.

Chuck Wendig’s Miriam Black is an excellent example of this. A girl with a prophetic gift to see the death of those she touches, Miriam Black is being crushed under the weight of her own strange power when we meet her. She’s seen hundreds of horrific deaths, and can’t stop a single one from happening (she’s tried a lot — it doesn’t work.) She’s hardened into a caustic loner who actively avoids relationships of any kind, yet she’s not unlikeable. It’s a survival tactic, from years of being alone and on the road. Wendig makes you empathize with Miriam — even like her — and then she opens up her mouth and says something really sarcastic or judgmental to someone at exactly the wrong time, completely derailing herself and her objective. You will literally shake your head and say, “WHAT THE CRAP, MIRIAM???” in the middle of reading one of the Miriam Black books. Seriously, for an example of one of the best antiheroes you’ll ever read, check them out.

The antihero is not amoral; they care in spite of themselves. The antihero can’t do whatever he or she wants without consequence; they are their own worst enemy and their lives and their bad behavior makes their lives harder than it should be. A good antihero is doesn’t win the day in the traditional sense. They survive, they may even achieve their goals, but they don’t thrive from those achievements. The antihero endures to self-sabotage another day. And they are generally self aware enough to know they are assholes and feel bad about it.

Recent Comments